WikiLeaks on Tuesday dropped one of its most explosive word bombs ever: A secret trove of documents apparently stolen from the

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)

detailing methods of hacking everything from smart phones and TVs to

compromising Internet routers and computers. KrebsOnSecurity is still

digesting much of this fascinating data cache, but here are some first

impressions based on what I’ve seen so far.

First, to quickly recap what happened: In a post on its site, WikiLeaks said the release —

dubbed “Vault 7”

— was the largest-ever publication of confidential documents on the

agency. WikiLeaks is promising a series of these document caches; this

first one includes more than 8,700 files allegedly taken from a

high-security network inside

CIA’s Center for Cyber Intelligence in Langley, Va.

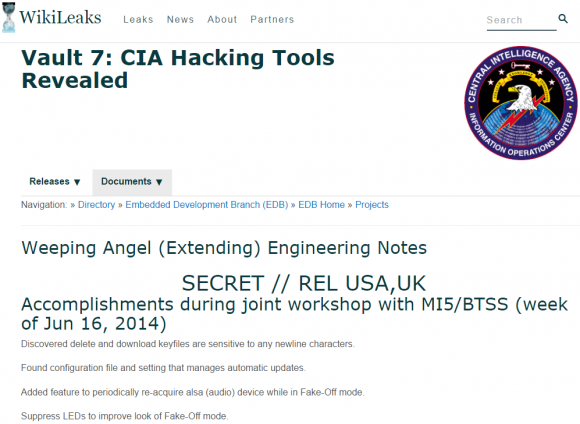

The

home page for the CIA’s “Weeping Angel” project, which sought to

exploit flaws that could turn certain 2013-model Samsung “smart” TVs

into remote listening posts.

“Recently, the CIA lost control of the majority of its hacking

arsenal including malware, viruses, trojans, weaponized ‘zero day’

exploits, malware remote control systems and associated documentation,”

WikiLeaks wrote. “This extraordinary collection, which amounts to more

than several hundred million lines of code, gives its possessor the

entire hacking capacity of the CIA. The archive appears to have been

circulated among former U.S. government hackers and contractors in an

unauthorized manner, one of whom has provided WikiLeaks with portions of

the archive.”

Wikileaks said it was calling attention to the CIA’s global covert

hacking program, its malware arsenal and dozens of weaponized exploits

against “a wide range of U.S. and European company products, includ[ing]

Apple’s iPhone, Google’s Android and Microsoft’s Windows and even

Samsung TVs, which are turned into covert microphones.”

The documents for the most part don’t appear to include the computer

code needed to exploit previously unknown flaws in these products,

although WikiLeaks says those exploits may show up in a future dump.

This collection is probably best thought of as an internal corporate

wiki used by multiple CIA researchers who methodically found and

documented weaknesses in a variety of popular commercial and consumer

electronics.

For example, the data dump lists a number of exploit “modules”

available to compromise various models of consumer routers made by

companies like

Linksys,

Microtik and

Zyxel,

to name a few. CIA researchers also collated several pages worth of

probing and testing weaknesses in business-class devices from

Cisco, whose powerful routers carry a decent portion of the Internet’s traffic on any given day.

Craig Dods, a researcher with Cisco’s rival

Juniper,

delves into greater detail

on the Cisco bugs for anyone interested (Dods says he found no exploits

for Juniper products in the cache, yet). Meanwhile, Cisco has

published its own blog post on the matter.

WHILE MY SMART TV GENTLY WEEPS

Some of the exploits discussed in these leaked CIA documents appear

to reference full-on, remote access vulnerabilities. However, a great

many of the documents I’ve looked at seem to refer to attack concepts or

half-finished exploits that may be limited by very specific

requirements — such as physical access to the targeted device.

The “

Weeping Angel”

project’s page from 2014 is a prime example: It discusses ways to turn certain 2013-model

Samsung

“smart TVs” into remote listening devices; methods for disabling the

LED lights that indicate the TV is on; and suggestions for fixing a

problem with the exploit in which the WiFi interface on the TV is

disabled when the exploit is run.

ToDo / Future Work:

Build a console cable

Turn on or leave WiFi turned on in Fake-Off mode

Parse unencrypted audio collection

Clean-up the file format of saved audio. Add encryption??

According to the documentation, Weeping Angel worked as long as the

target hadn’t upgraded the firmware on the Samsung TVs. It also said the

firmware upgrade eliminated the “current installation method,” which

apparently required the insertion of a booby-trapped USB device into the

TV.

Don’t get me wrong: This is a serious leak of fairly sensitive

information. And I sincerely hope Wikileaks decides to work with

researchers and vendors to coordinate the patching of flaws leveraged by

the as-yet unreleased exploit code archive that apparently accompanies

this documentation from the CIA.

But in reading the media coverage of this leak, one might be led to

believe that even if you are among the small minority of Americans who

have chosen to migrate more of their communications to privacy-enhancing

technologies like

Signal or

WhatsApp, it’s all futility because the CIA can break it anyway.

Perhaps a future cache of documents from this CIA division will

change things on this front, but an admittedly cursory examination of

these documents indicates that the CIA’s methods for weakening the

privacy of these tools all seem to require attackers to first succeed in

deeply subverting the security of the mobile device — either through a

remote-access vulnerability in the underlying operating system or via

physical access to the target’s phone.

As Bloomberg’s tech op-ed writer

Leonid Bershidsky notes,

the documentation released here shows that these attacks are “not about

mass surveillance — something that should bother the vast majority of

internet users — but about monitoring specific targets.”

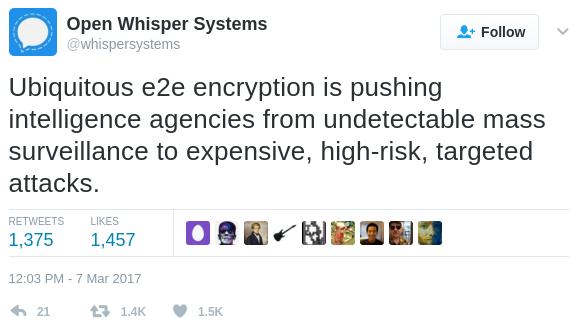

By way of example, Bershidsky points to

a tweet yesterday from

Open Whisper Systems

(the makers of the Signal private messaging app) which observes that,

“The CIA/Wikileaks story today is about getting malware onto phones,

none of the exploits are in Signal or break Signal Protocol encryption.”

The company went on to say that because more online services are now

using end-to-end encryption to prevent prying eyes from reading

communications that are intercepted in-transit, intelligence agencies

are being pushed “from undetectable mass surveillance to expensive,

high-risk, targeted attacks.”

A tweet from Open Whisper Systems, the makers of the popular mobile privacy app Signal.

As limited as some of these exploits

appear to be, the methodical approach of the countless CIA researchers

who apparently collaborated to unearth these flaws is impressive and

speaks to a key problem with most commercial hardware and software

today: The vast majority of vendors would rather spend the time and

money marketing their products than embark on the costly, frustrating,

time-consuming and continuous process of stress-testing their own

products and working with a range of researchers to find these types of

vulnerabilities before the CIA or other nation-state-level hackers can.

Of course, not every company has a budget of hundreds of millions of dollars just to do basic security research. According to

this NBC News report

from October 2016, the CIA’s Center for Cyber Intelligence (the alleged

source of the documents discussed in this story) has a staff of

hundreds and a budget in the hundreds of millions: Documents leaked by

NSA whistleblower

Edward Snowden indicate the CIA requested $685.4 million for computer network operations in 2013, compared to $1 billion by the

U.S. National Security Agency (NSA).

TURNABOUT IS FAIR PLAY?

NBC also reported that the CIA’s Center for Cyber Intelligence was

tasked by the Obama administration last year to devise cyber attack

strategies in response to Russia’s alleged involvement in the siphoning

of emails from

Democratic National Committee servers as well as from

Hillary Clinton‘s campaign chief

John Podesta. Those emails were ultimately published online by Wikileaks last summer.

the “wide-ranging ‘clandestine’

cyber operation designed to harass and ’embarrass’ the Kremlin

leadership was being lead by the CIA’s Center for Cyber Intelligence.”

Could this attack have been the Kremlin’s response to an action or

actions by the CIA’s cyber center?

NBC reported that

the

“wide-ranging ‘clandestine’ cyber operation designed to harass and

’embarrass’ the Kremlin leadership was being lead by the CIA’s Center

for Cyber Intelligence.” Could this attack have been the Kremlin’s

response to an action or actions by the CIA’s cyber center? Perhaps time (or future leaks) will tell.

Speaking of the NSA, the Wikileaks dump comes hot on the heels of a similar disclosure by

The Shadow Brokers, a hacking group that said it stole malicious software from the

Equation Group, a highly-skilled and advanced threat actor that has been closely tied to the NSA.

What’s interesting is this Wikileaks cache includes

a longish discussion thread

among CIA employees who openly discuss where the NSA erred in allowing

experts to tie the NSA’s coders to malware produced by the Equation

Group. As someone who spends a great deal of time

unmasking cybercriminals who invariably leak their identity and/or location through poor operational security, I was utterly fascinated by this exchange.

BUG BOUNTIES VS BUG STOCKPILES

Many are using this latest deluge from WikiLeaks to reopen the debate

over whether there is enough oversight of the CIA’s hacking

activities.

The New York Times called

yesterday’s WikiLeaks disclosure “the latest coup for the antisecrecy

organization and a serious blow to the CIA, which uses its hacking

abilities to carry out espionage against foreign targets.”

The WikiLeaks scandal also revisits the question of whether the U.S.

government should instead of hoarding and stockpiling vulnerabilities be

more open and transparent about its findings — or at least work

privately with software vendors to get the bugs fixed for the greater

good. After all, these advocates argue, the United States is perhaps the

most technologically-dependent country on Earth: Surely we have the

most to lose when (not if) these exploits get leaked? Wouldn’t it be

better and cheaper if everyone who produced software sought to

crowdsource the hardening of their products?

On that front, my email inbox was positively peppered Tuesday with

emails from organizations that run “bug bounty” programs on behalf of

corporations. These programs seek to discourage the “full disclosure”

approach — e.g., a researcher releasing exploit code for a previously

unknown bug and giving the affected vendor exactly zero days to fix the

problem before the public finds out how to exploit it (hence the term

“zero-day” exploit).

Rather, the bug bounties encourage security researchers to work

closely and discreetly with software vendors to fix security

vulnerabilities — sometimes in exchange for monetary reward and

sometimes just for public recognition.

Casey Ellis, chief executive officer and founder of bug bounty program

Bugcrowd,

suggested the CIA WikiLeaks disclosure will help criminal groups and

other adversaries, while leaving security teams scrambling.

“In this mix there are the targeted vendors who, before today, were

likely unaware of the specific vulnerabilities these exploits were

targeting,” Ellis said. “Right now, the security teams are pulling apart

the Wikileaks dump, performing technical analysis, assessing and

prioritizing the risk to their products and the people who use them, and

instructing the engineering teams towards creating patches. The net

outcome over the long-term is actually a good thing for Internet

security — the vulnerabilities that were exploited by these tools will

be patched, and the risk to consumers reduced as a result — but for now

we are entering yet another Shadow Brokers, Stuxnet, Flame, Duqu, etc., a

period of actively exploitable 0-day bouncing around in the wild.”

Ellis said that — in an ironic way, one could say that Wikileaks, the

CIA, and the original exploit authors “have combined to provide the

same knowledge as the ‘good old days’ of full disclosure — but with far

less control and a great many more side-effects than if the vendors were

to take the initiative themselves.”

“This, in part, is why the full disclosure approach evolved into the coordinated disclosure and

bug bounty

models becoming commonplace today,” Ellis said in a written statement.

“Stories like that of Wikileaks today are less and less surprising and

to some extent are starting to be normalized. It’s only when the pain of

doing nothing exceeds the pain of change that the majority of

organizations will shift to an proactive vulnerability discovery

strategy and the vulnerabilities exploited by these toolkits — and the

risk those vulnerabilities create for the Internet — will become less

and less common.”

Many observers — including a number of cybersecurity professional

friends of mine — have become somewhat inured to these disclosures, and

argue that this is exactly the sort of thing you might expect an agency

like the CIA to be doing day in and day out.

Omer Schneider, CEO at a startup called

CyberX, seems to fall into this camp.

“The main issue here is not that the CIA has its own hacking tools or

has a cache of zero-day exploits,” Schneider said. “Most nation-states

have similar hacking tools, and they’re being used all the time. What’s

surprising is that the general public is still shocked by stories like

these. Regardless of the motives for publishing this, our concern is

that Vault7 makes it even easier for a crop of new cyber-actors get in

the game.”

TalkTalk has

blocked remote desktop management tool TeamViewer from its network,

following a spate of scammers using the software to defraud customers.

TalkTalk has

blocked remote desktop management tool TeamViewer from its network,

following a spate of scammers using the software to defraud customers.