The detection and blocking of malicious

code employed by modern threats, whether targeted attacks or

mass-spreading campaigns, has been a game of cat-and-mouse with the

perpetrators for some time now. And even though we are seeing shifts in

the threat landscape and new malware trends, the “malware problem” is

still very much with us. To be clear, most malware writing today is

performed by, or purchased by, cross-border criminal organizations. We

are no longer faced with a few over-enthusiastic individuals. That means

most malware attacks are functional and to some degree effective, in

other words: people get infected. These attacks are generally low-risk

and often very profitable.

The development of anti-malware defenses

As malicious code threats have evolved over the years, so

have the technologies deployed to protect against them. The traditional

concept of an “anti-virus” program has evolved into more comprehensive

“security suites.” These suites include, in addition to traditional

anti-malware scanners, firewalls, HIPS (Host Intrusion Prevention

Systems), and other technologies.

One of the reasons such multi-layered protection is

necessary is that the “bad guys” have the advantage of only needing to

find one hole in our defenses, while companies and consumers need

protection across many different points of attack. Security companies

like ESET are consistently monitoring the evolution of malware families

and collecting new samples of malicious code. The servers in the ESET

Security Research Lab receive over 200000 unique malicious binaries

every day, malware detected proactively, that we have never seen before.

Even so, we don’t really see all the cards in the game. Malware

writers, on the other hand, have access to all of the commonly used

security solutions. They use this access to tweak their code so that it

is harder to detect when it is released.

Of course, our job is to defeat that process. We want to

make it impossible, or at least more difficult and expensive, for

malware writers to craft code that is not detected. This requires

additional layers of security that introduce creative strategies that

can catch malicious code which might evade basic defenses.

One strategy that has been around for some time is advanced heuristics, explained in detail by Righard Zwienenberg on WeLiveSecurity.com. There is also an ESET white paper on basic heuristics.

In this article we expand on the heuristic approach, and introduce some

additional strategies that security software can deploy to combat

malware. We begin by explaining several particularly challenging

techniques used by malware writers today.

Malware protectors

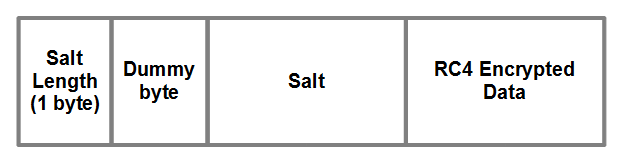

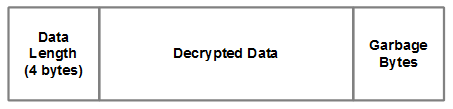

The main technique employed by malware writers in order to

avoid detection by antivirus software is the use of various “protectors”

or run-time packers.

You can think of these protectors as outer shells of the executables

that hide the inner payload from inspection, and therefore detection, by

basic anti-virus scanners.

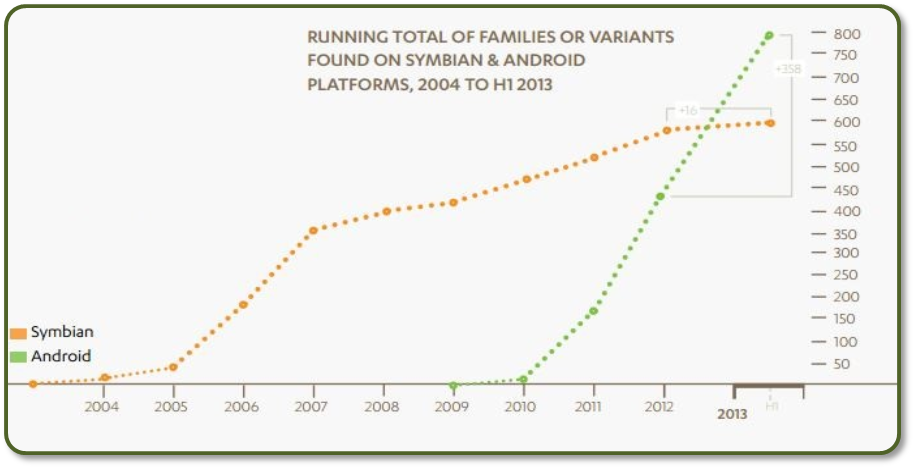

That explains why, out of the many thousands of fresh

malware samples that we see daily in our lab, relatively few contain new

functionalities. Most of those daily unique samples are repackaged

versions of existing malware families. The frequent repacking of malware

variants is also known as server-side polymorphism.

An antivirus program that relies solely on simple

hash-based signature detection of previously known malware can be

defeated by the ever-changing malware. Furthermore, such detection is

very inefficient. That is why a great amount of research has been done

in order to crack that outer shell of malware protection using

emulation. The idea is to run potentially malicious executables in a

virtual environment or sand box, where they won’t be able to cause

damage to the system and user, but will become unpacked and can be

caught by the anti-virus engine.

While this might sound simple in theory, in reality there

are several challenges that must be overcome for this to work, and a

number of potential drawbacks that must be taken into consideration:

-

The malware can attempt to hinder emulation, for example by use of uncommon instructions or API functions, which the emulator didn’t expect and can’t handle correctly.

-

The malware can detect it is being run in a virtual environment and either stop executing or continue in a benign mode to avoid detection.

-

Even if the code is emulated correctly, it can still be obfuscated in such a way that it hides its malicious functionality and its detection is still problematic.

-

Emulation or any virtualization technology always carries with it some negative performance impact.

One significant method for improvement of emulation (with respect to the problematic aspects mentioned above) is by employing binary translation.

One of the most infamous banking Trojans, Zeus (detected by ESET as Win32/Spy.Zbot)

is a good example of how repacking with various protectors has proven

to be effective for the bad guys. This is malware that has been widely

known for at least six years and its source code was leaked back in

2011. Yet Zeus often succeeds in evading detection by anti-malware

scanners, because of the advanced packers used by the gangs that build

and operate Zeus.

For cases when inspection of the protected and obfuscated

sample prior to its execution is not successful, antivirus software has

one last chance of detecting it: when it is running in memory in a

decloaked state. Yet again, the challenge for security companies lies in

triggering appropriate memory scanning as soon as possible, so that the

malware causes minimal damage. This needs to be done with as little

negative impact on system performance as possible.

Exploitation as an infection vector

Clearly, it is more desirable to prevent a malware

infection even before it sets foot on the target system. There are many

different infection vectors and, like malware itself, these have also

evolved over time. However, generally they can be grouped into two

categories:

-

With user interaction: the victim is led to the infection through social engineering

-

Without user interaction: mostly through exploits of software vulnerabilities

The subject of social engineering is a broad one and is a frequent topic of We Live Security blog posts. Here we will focus on software exploitation, without user interaction.

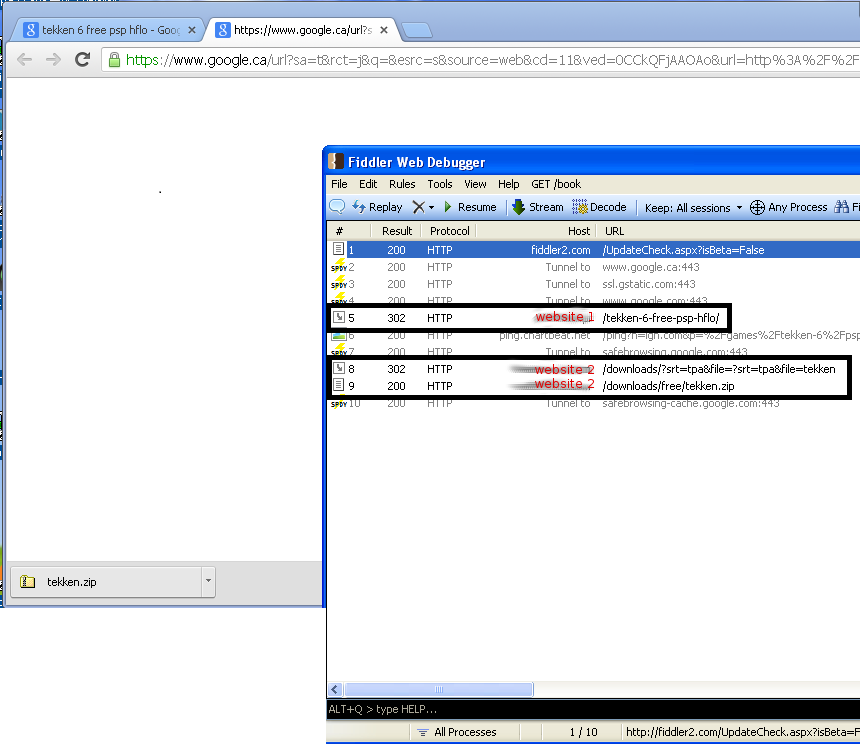

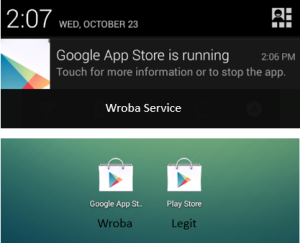

A typical scenario is that a user navigates to a webpage,

subverted by an attacker, that contains a malicious script calling an

exploit pack or exploit kit (something we have covered in various articles).

Simply put, the exploit pack is a web app that will first check the

potential victim’s software versions. This can be accomplished by

legitimate scripts, such as PluginDetect.

Then, if an unpatched, vulnerable version is detected, an exploit will

be served and malicious code can be executed on the system without the

user ever noticing anything. From the attacker’s point of view this is a

very effective way of infecting even the more cautious users. For this

reason, the underground market where cybercriminals buy exploit kits and

new software vulnerabilities is thriving.

The obvious protection against these kinds of attacks is to

patch the software vulnerabilities, but unfortunately people patch

slowly and some don’t patch at all. Furthermore, patching is not

effective against zero-day exploits, those that are unknown to the

affected software vendor and for which no patch is available at the time

of the attack.

Signature-based detection can be used to detect exploit

code, but it suffers from the same shortcomings as when used against

“regular” malware, so more generic detection and mitigation approaches

are needed.

One example of a mitigation tool is EMET

(Enhanced Mitigation Experience Toolkit) from Microsoft. EMET makes

life much more difficult for exploits (in fact, renders many of them

defunct) by protecting against common techniques used by exploits and

forcing built-in Windows security measures, namely DEP (Data Execution Prevention), ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) and SEHOP (structured exception handler overwrite protection).

Modern antivirus solutions introduce a more generic

behavior-based approach, inspecting the very act of exploitation and

checking if, for example, a (malicious) process is spawned in

a suspicious manner that‘s not typical for the host application. This

technology can block advanced and reliable exploitation techniques,

typically bundled in today’s professional exploit kits.

One of such examples is CVE-2013-0641, which was the winner of the 2013 Pwnie Awards

at the BlackHat conference for the most technically sophisticated and

interesting client-side bug. This exploit targeted Adobe Reader and was

able to escape its sandbox. Apart from PDF readers, the other most

exploited applications by malware include internet browsers and their

plugins, Flash players, Java and MS Office components. This kind of

approach can also help prevent zero-day exploits.

But blocking exploits doesn’t only have to take place at

the process level. For example, many worms still rely on network

protocol vulnerabilities in order to spread. While there are many more

fresh examples of this, the most infamous one is probably the Conficker

worm exploiting MS08-067 through a specially crafted RPC call. Despite

the fact that this vulnerability has been patched for 5 years now, our LiveGrid telemetry

shows us that the exploit is still widely used in the wild. This

indicates that adding another, network layer to the protection stack, is

also beneficial.

Conclusion

We’ve addressed some of the technical tricks that malware

authors use to successfully infiltrate target systems without being

detected. The descriptions above apply both to mass-scale attacks, as

well as customized targeted attacks, with an important side-note. A

targeted attack is much more difficult to prevent, since the attacker

knows his victim and can tailor the attack using very focused social

engineering and exploits against the exact software that the victim is

running, and so on. Targeted attacks especially highlight the importance

of multi-layered security and the usefulness of generic exploitation

detection.